When I was a kid, I read Hello! magazine voraciously. I was an avid follower of the endless social engagements of minor aristos and other colourful figures on the London scene at the end of the last century (despite not really knowing what the scene was), and I developed an in-depth knowledge of the private members clubs and polo engagements that these people frequented. A fairly odd choice of reading matter for a 10-year-old, but I was fascinated. Everyone looked so glamorous. Everyone looked so rich.

“What’s the use of happiness? It can’t buy you money.” An old joke from Henny Youngman, king of the one-liner, but it still resonates. Youngman, born in Britain, made his fortune in America, which tells you everything. Why is it exactly that we – those of us who remain on this class-obsessed, status-plagued island which has always been fascinated with money – are largely terrible at actually being able to talk about cash? Why was I quietly reading magazines in my childhood bedroom, enamoured by the lifestyles of the wealthy? I was lucky enough to be born into a fairly well-off family in London who never experienced anything close to poverty, and yet I looked at all those glossy people on all those glossy pages and the way they were living and wanted it for myself.

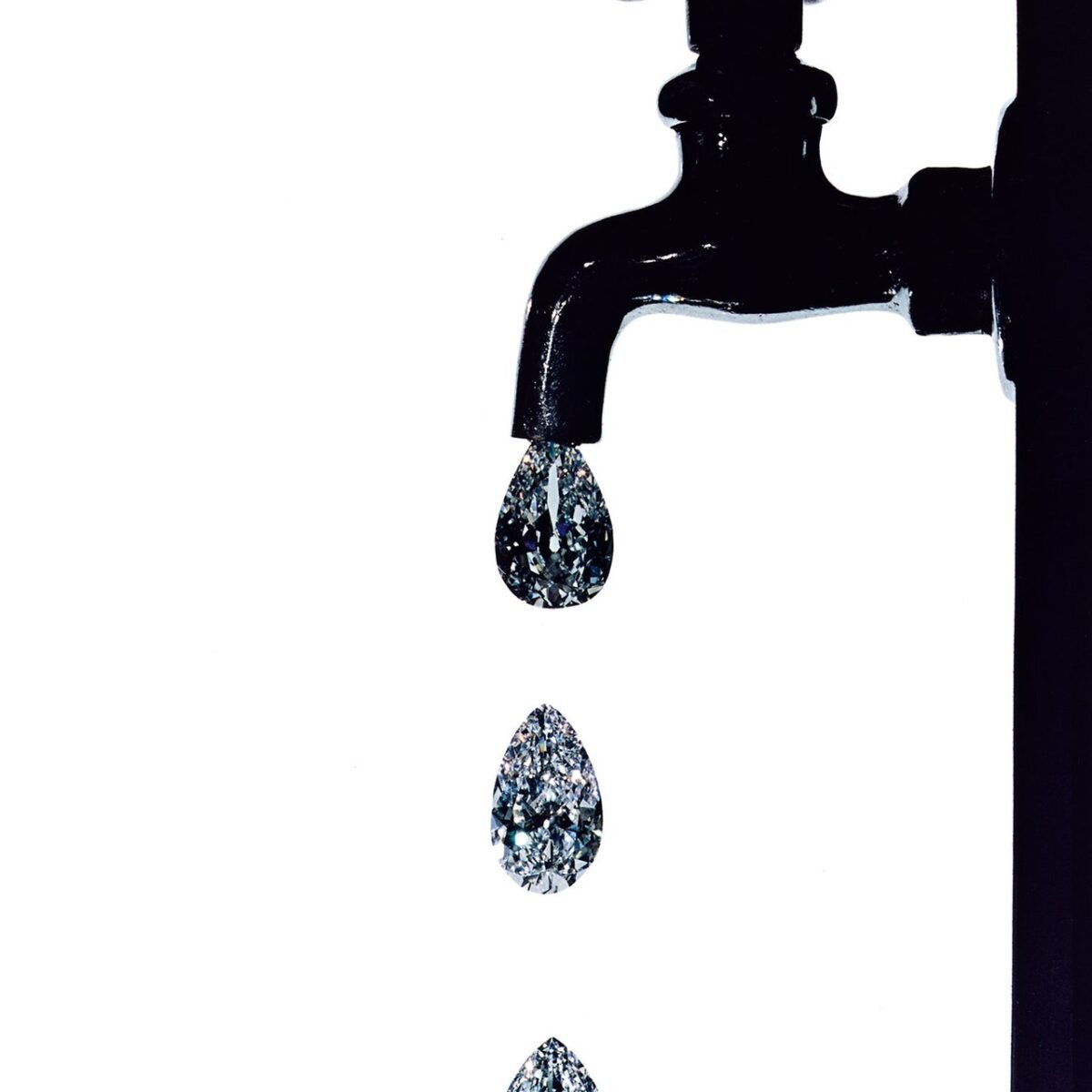

Are the majority of us not-so-secretly wired this way? Much of the culture we imbibe centres on the escapades of the rich, from contemporary television (The White Lotus, Buying London, Bridgerton) to the novels we’re spoon-fed at school (Great Expectations, The Great Gatsby, Atonement). Surely our obsession with the trappings and minutiae of the one per cent has something to say about how we deal with the complicated emotions surrounding our own finances.

My new novel, What a Way To Go, centres around wealth and the way its very presence controls relationships. The family at the centre of the story are fawned over, respected and feted for no other reason than that they are rich. When the money slips away, they face having to have awkward and hostile conversations about it for the first time. American novelist Taffy Brodesser-Akner has chosen a similar theme with which to follow up her 2019 blockbuster Fleishman is in Trouble. This month, she publishes Long Island Compromise, a bleakly comic story about the Fletcher family and the myriad ways in which their mountains of money have ruined them. “They never talked about what all this money did to them,” Brodesser-Akner writes, “how it made them look to others, or how it felt for them to have it, how they behaved because of all of it.” (Just like Fleishman, her new novel has already been snapped up for a big, lustrous TV adaptation.)

And then there’s bestselling novelist Rumaan Alam (his last book, Leave The World Behind, was turned into a film starring Julia Roberts), who’s back in September with the “taut and unsettling” Entitlement – a story “alive to the seductive distortions of money”, described as “a biting tale for our new gilded age”. Meanwhile, in his upcoming book, Money: A Story of Humanity, economist David McWilliams also looks at how it changes us; how, over the past 5,000 years, it has shaped the very essence of what it means to be human. Our bank balance is, he says, an emotional nexus. “Money buys independence. Money is power, it is domination but it can also be liberation… Money doesn’t impose on human morals; it amplifies them. If a person believes greed is good, they will behave accordingly.”