To learn about initial public offerings and dividends, try the 18XX series of games that recreate the 19th-century railway booms. Those booms helped develop and create public companies, the stock market and even the banking system that are still much the same today.

In Iberian Gauge, for example, players buy shares in IPOs of five railways on the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal).

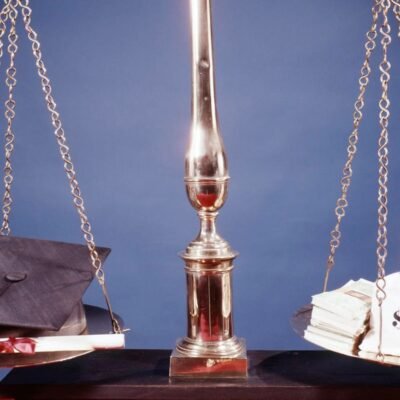

Players learn that the initial price of the railway company’s shares has to be high enough to give it the capital it needs to build railways, but low enough to attract investors. That’s a challenge investment bankers face every day.

Once bought, players receive dividends, As directors of the railway companies, they also have to decide on the profit payout ratio – i.e. how much to pay as dividends and how much to reinvest in building railways (and so eventually pay higher dividends). That’s a key tool of stock valuation and selection in real life.

Short selling

In 1830: Railways and Robber Barons, the gameplay emphasis is on manipulating the sharemarket, although players can also win by buying and holding shares in rival companies and investing traditionally.

One of the key strategies is to buy stock in a rival’s company and immediately sell it, thus making a profit for you and driving down the rival’s share price. This is as close as any game gets to short-selling – a key practice of many hedge funds. Other games in this genre that explore this concept include 18 Chesapeake, Shikoku 1889 and 18Mex.

How to spot a bad company

Railways and Robber Barons also include play on banned practices such as insider trading, asset stripping and pumping and dumping.

By showing how companies can be manipulated, the games teach useful skills to help you spot potentially bad investments.

Players who own the majority shareholdings in the railways in the game are free to act in a way that doesn’t benefit other shareholders. While in real life, institutions like APRA and ASIC give minor shareholders some protections, Robber Barons basically gives a master class in shady practices to look out for.

For example, a major shareholder can strip money out of the company. It can do this by paying another company too much for assets, or the major shareholder and chairman might use your company’s assets to build a railway that might benefit another company that the chairman controls.

For a game that takes this to the next level, you cannot go past Jack Company. In this game, players work for the most successful and rapacious company of all time – the British East India Company. Players get an understanding of almost every bad practice that real-life companies do. It’s a fraud masterclass for would-be ASIC employees.

Asset selection

One of the best ways to learn about what assets to buy and sell are capital allocation games like City of the Big Shoulders and Brass Birmingham.

By securing raw materials to make products, selling and trading in them, the game teaches skills that directly relate to picking investments.

In City of the Big Shoulders players take on the challenge of rebuilding Chicago after a fire wiped out much of the downtown (this actually happened in Chicago). In doing so they create companies and brands that still exist today such as Kraft, Nabisco and Charles Schwab. It’s a 101 course on how capitalism works

Brass Birmingham, in which players first build a canal network and then a rail network, teaches players about obsolescence and how to prepare for how a game-changing technology might upend previously profitable investments. For a real-life proposition here, think about how artificial intelligence is changing the investing world today.

Trading

For the bare knuckles of buying and selling assets in a market with limited information, the game of QE is hard to beat.

Mark Bainey loved Monopoly as a kid. Louie Douvis

QE sees players control governments and central banks in a perpetual COVID-19 blowout. They bid in silent auctions to buy companies, bonds, and commodities. They have unlimited budgets because they can print their own money.

But at the end of the game, if they have bid too much for those assets, they get swamped by inflation and lose. Maybe a few central bankers should have played this one.

There are also games that directly relate to stock trading like Stockpile and Acquire, or commodity market games such as Pit. In Pit, for example, players are traders on the Chicago Board of Exchange. The aim is to corner the market in a commodity to create a monopoly.

Which brings us back to Monopoly and Steve McMenamin’s winning strategy before he started House Land Co.

“I played the game a lot as a kid, I used to buy up all the sets.”

McMenamin says he bought his first house at 19 for $29,000 in the “Old Kent Road” part of the Gippsland town of Sale. After buying a few more properties and developing them, he bought his “Mayfair” at Oxford Court in Traralgon.