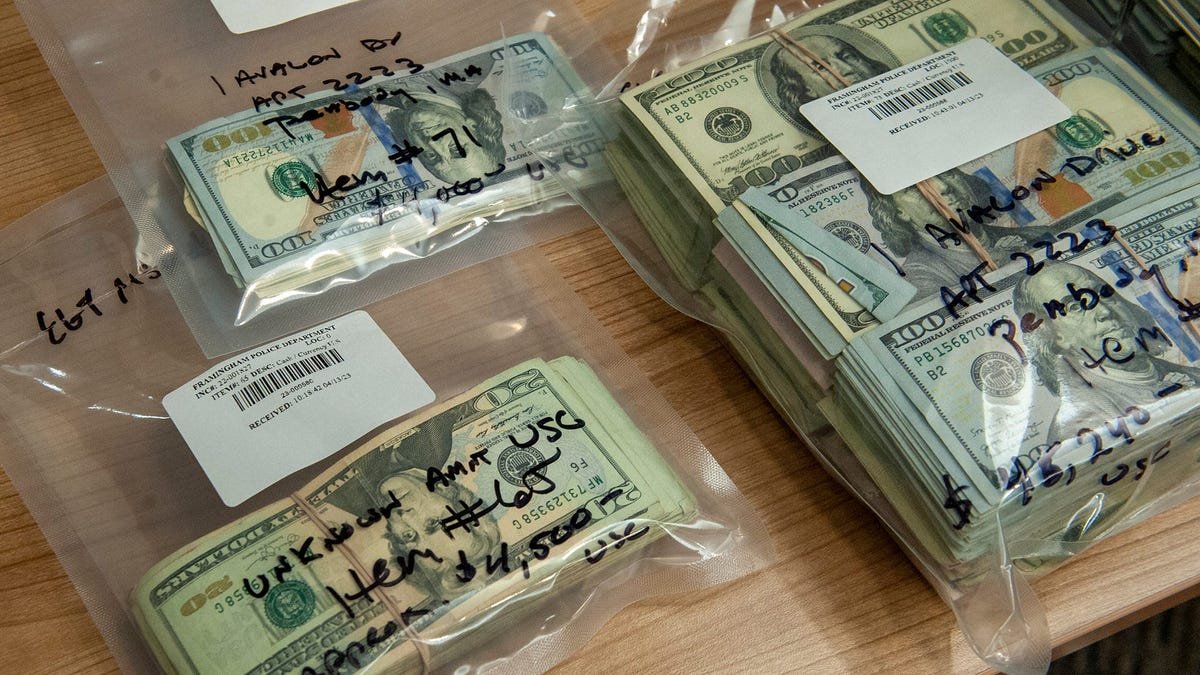

Police raid finds no drugs, but officers leave with thousands in cash

Police raided Miguel Zeldon’s home in Philadelphia looking for drugs. No drugs were found, but police confiscated thousands of dollars in cash.

Jack Gruber, USA TODAY

California husband and wife Henry and Minh Cheng own a jewelry business, and earlier this year they sold a bulk order of gold chains to a retailer in Virginia, which agreed to mail $43,000 in exchange. The money never made it.

Police officers in Indiana, where the package was routed through a FedEx shipping facility, seized the cash. Neither the Chengs nor the Virginia retailer were charged with a crime, the nonprofit law firm representing them says, but the government took the money, claiming that large shipments of cash are usually associated with criminal activity.

Now the couple, backed by nonprofit Institute for Justice, is suing the state in a class action suit filed earlier this month claiming a widespread pattern of unlawful package seizures at the facility.

Law enforcement was able to take the money through a controversial practice called civil asset forfeiture. Advocates against the practice say it amounts to legalized government theft, at times from ordinary, innocent Americans.

Some government officials disagree, saying the power to seize cash, cars and even houses allows the government to cut off criminals’ resources and disincentivize crime, especially as it relates to drug trafficking.

It “helps law enforcement defund organized crime, take back ill-gotten gains, and prevent new crimes from being committed, and it weakens the criminals and the cartels,” former Attorney General Jeff Sessions said when he expanded the practice in 2017.

Critics say it’s become a booming source of profit for law enforcement, who in many states pocket most of the proceeds.

In 2020, police seized nearly $40,000 in cash from Jerry Johnson at the Phoenix airport, where he was traveling to buy a semi truck in cash for his shipping business. It took him two-and-a-half years of battling the government to get the money back.

“Ordinary Americans who have done no wrong are at risk,” said University of Pennsylvania law professor Louis Rulli. “Just because you haven’t done anything wrong does not mean you’re safe from civil forfeiture, and it’s very costly and very difficult to fight the government.”

What is civil forfeiture? Why does it exist?

The concept behind civil forfeiture in the U.S. dates back to the founding of the American republic, when it was common for European-owned ships to engage in smuggling and customs violations. With the owners outside the jurisdictions of American courts, the seizing of property was a way for the U.S. government to enact their own penalties.

Its original intention has warped, and now instead of targeting large criminal networks, it’s often used against everyday citizens while netting billions in annual forfeitures, Rulli said. That includes everything from forfeitures in larger drug raids and smaller amounts taken from individuals at traffic stops.

In the 1970s and 80s, civil forfeiture shifted to become a tool for the “war on drugs.” In addition to drugs and drug-dealing paraphernalia, law enforcement began using civil forfeiture to seize cash and belongings from suspected drug criminals.

More: From pirates to kingpins, the strange legal history of civil forfeiture

Civil forfeiture laws vary by state, but in general, they allow for law enforcement to seize property or belongings that they believe may be involved in the commission of a crime. The owner of the assets need not be convicted, or even accused, of an actual crime.

Police commonly seize money, homes and cars, but have also taken odd items like a tattoo gun, night vision goggles, and a washer and dryer set.

In Aiken County, South Carolina, sheriff’s deputies discovered 29 marijuana plants growing and seized the landowner’s tractor, which was valued at $24,000. Authorities said it had been used to water the marijuana plants.

The tractor’s owner, Dennis Ruff, fought for three years in court to get it back without success – he also never faced charges as of 2019.

Because of a quirk in civil forfeiture cases, owners have little recourse to fight in court, Rulli said. Action is taken against the property itself, not against a person, he said. You may see court cases titled “State v. $10,000,” for example, according to Rulli.

That means property owners don’t have the right to legal defense, and would often have to spend more than the property is worth on lawyers fighting the seizure. In many states, the burden of proof on the government isn’t “beyond a reasonable doubt,” the way it would be in a criminal case.

Can innocent people have their property taken by cops?

Rulli runs a legal clinic for low-income people in Philadelphia and has taken on many civil forfeiture cases. He said one of the most common ways these cases play out is on interstate highways. Police do routine traffic stops, search cars, and despite finding no evidence or drug activity, seize cash they find within.

There’s a racial and poverty dynamic to civil forfeiture, he said.

“If so much of civil forfeiture is stopping motorists on highways, we know that minorities are stopped at higher rates,” Rulli said.

He’s also seen many instances in Philadelphia of elderly people having their homes seized by the government because perhaps, unbeknownst to them, their grandchild sold marijuana to an undercover cop from their front porch or the sidewalk down the block.

Research by the Institute for Justice shows that owners with seized property rarely fight back. Rulli said that’s because it costs too much, takes too much time, and can be intimidating to go up against the government. The nonprofit has also surveyed hundreds of people who had property taken through civil forfeiture and found that the majority were never charged with crimes.

There is also such a thing as criminal forfeiture, Rulli said, which is the taking of someone’s property when they have been convicted of a crime.

“I think folks recognize that there can be appropriate times that property should be taken, but only after someone has been proven guilty,” he said.

It’s not clear how many Americans are impacted each year, as states track and report information differently.

Ordinary Americans get ‘swept up’ in civil forfeiture

Philadelphia resident Nassir Geiger paused his car in a parking lot one night in 2014 to say hello to a friend, who had recently been arrested for drug possession. Police stopped Geiger and searched his car. Despite finding no evidence of drugs, they seized both the car and about $580 in cash.

“I didn’t break no traffic laws; my license wasn’t expired,” Geiger previously told USA TODAY. “For no reason, (the police) took my car.”

Rozina Javis fought the forfeiture of her home a decade ago, which was only dropped by the Richland County, South Carolina, Sheriff’s Department after she lawyered up. Deputies told the grandmother there was too much crime happening on her property, by her relatives and others who would gather at her home or on nearby sidewalks. Though she kept her home, she ended up in bankruptcy and said the cost to fight the forfeiture was too much.

“This is all I’ve got,” Javis told the Greenville News, part of the USA TODAY Network, years later.

Massachusetts resident Malinda Harris wrote in a USA TODAY opinion article about her car being taken by police after her son, who had borrowed the car, was accused of selling drugs. It took years to get the car back, she wrote in 2021.

“Ordinary Americans are finding themselves swept up in civil forfeiture in ways that really stretches the Constitution,” Rulli said.

Civil forfeiture necessary to curb crime, some say

Though many states have attempted to push through reforms to civil forfeiture laws in the last decade, the practice still has support among law enforcement agencies and district attorneys offices, who say it’s vital to combat crime.

A former member of the Reagan administration’s Department of Justice acknowledged in a USA TODAY opinion piece in 2017 that civil forfeiture can be subject to abuse by police, but argued that the process is fair to owners because they get notification and a chance to get their property back.

“Knowledge that money will be seized and not returned is an effective deterrent to committing more crime,” Alfred S. Regnery wrote.

The process varies by state and at the federal level, but in general, when law enforcement seizes money or property, police or a prosecutor files a motion in court to show why they believe the property was associated with a crime. Owners are generally notified and have a chance to respond, and a judge has the final say.

If the property is kept by the government, its proceeds usually go into law enforcement or state budgets. In South Carolina, for example, the property must be sold in a public auction and the profits are split between the police agency, the prosecutor and the state.

One South Carolina law enforcement officer explained why items seized might not always be drugs or money: “Drug dealers don’t always operate on a cash basis,” Chad Brooks, a captain in drug investigations at the Pickens County Sheriff’s Office, told the Greenville News, part of the USA TODAY Network. “Somebody may bring them a TV for a quarter ounce of meth, and a lot of times, they’ll admit to it.”

The Institute for Justice, which advocates against civil forfeiture, found that in the years after Nebraska effectively did away with the practice in favor of criminal forfeiture, crime rates did not go up.

Is change coming?

Civil forfeiture has been effectively eliminated in only North Carolina, Nebraska, New Mexico and Maine, according to the Institute for Justice. But dozens of other states have tried reforming their laws. Some have elevated the standard for burden of proof that law enforcement has to have to seize property. Others have improved the transparency of their procedures, Rulli said.

A federal loophole makes it easier for law enforcement agencies across the country to evade state reforms. The federal government isn’t beholden to state laws, Rulli said, so law enforcement agencies can call federal authorities in, which will seize property and split the profits with the local agencies.

Congress has been considering a measure called the Fifth Amendment Integrity Restoration (FAIR) Act, which would raise the standard of proof for the government; require counsel to be provided for someone who can’t afford it when their home is being taken; and prevent the evasion of state laws.

It’s a rare issue that has broad agreement between liberals and conservatives, Rulli said.

Most recently, the Supreme Court earlier this year disagreed that property owners are entitled to a preliminary hearing when police seize their property.

But some justices signaled they were open to a larger discussion about civil forfeiture. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, who usually sides with the court’s conservative majority, concurred with the ruling, but wrote there are “questions unresolved about whether, and to what extent, contemporary civil forfeiture practices can be squared with the Constitution’s promise of due process.”

Contributing: Tami Abdollah, USA TODAY; Perry Vandell, Arizona Republic; Ryan Murphy, Indianapolis Star; Anna Lee and Mike Ellis, Greenville News