Number 10, South Crescent, is an unremarkable London office building. About a five-minute walk north of Tottenham Court Road station, it is currently occupied by a construction consultancy. And yet it has caught the attention of Great Portland Estates (GPE), a London office real estate investment trust (Reit), which recently purchased it for £51mn.

When the sitting tenant’s lease expires in four years, GPE hopes it can develop the building and lease it at around double the existing rent, which would equate to a bumper 14 per cent yield on the purchase price. Deals such as South Crescent might hint at an increasingly favourable market for London office investors. But the reality is more nuanced.

Are rents growing?

‘Rental growth’ is understandably the favourite phrase of London office insiders at the moment. “Rental growth has been beyond robust and continues to be so,” says Hunter Booth, a director in Savills’ office business. “The demand that we track has never been higher.”

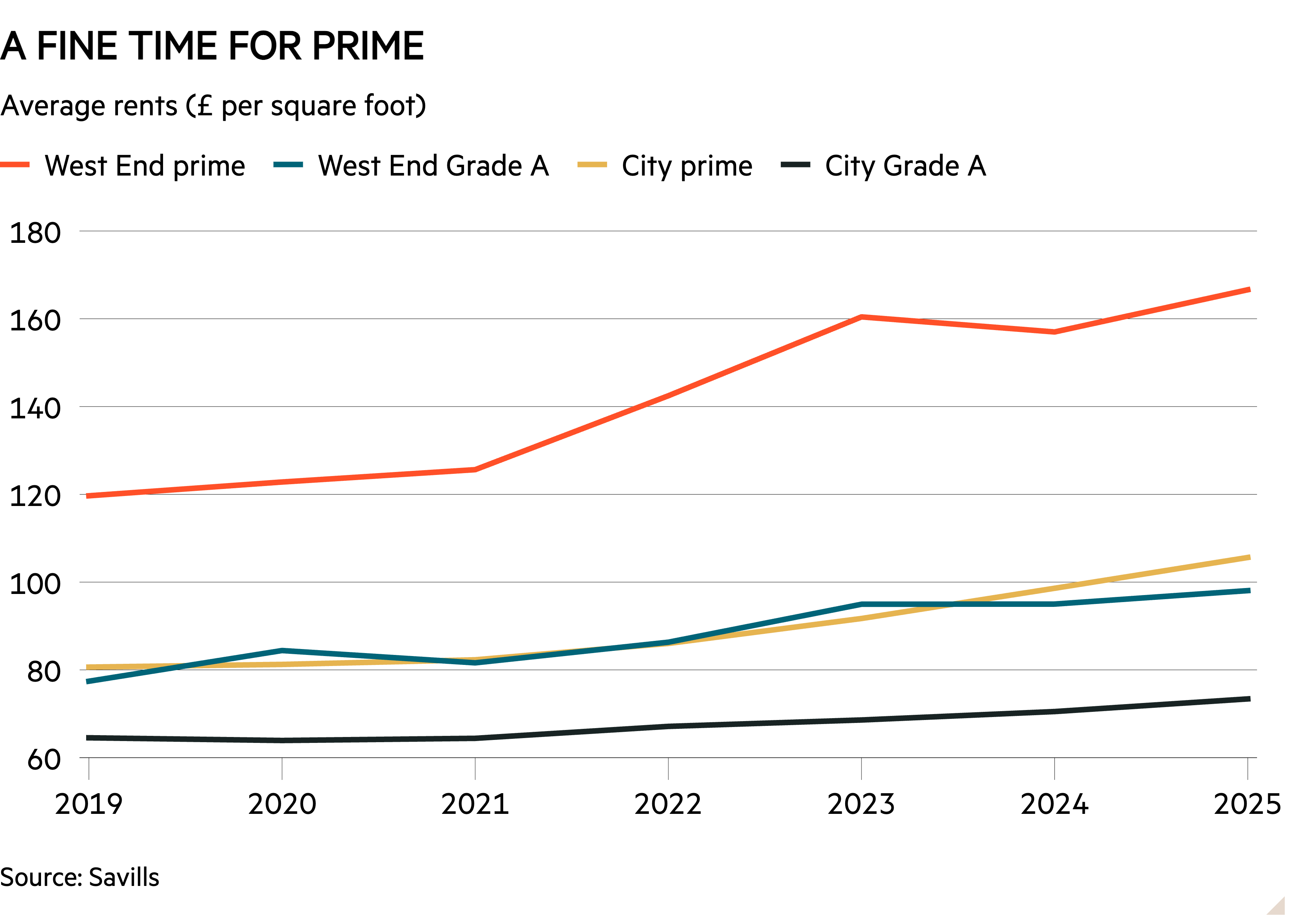

Rents for prime offices in London’s West End and the City have grown at annual rates of 7 per cent and 6 per cent, respectively, since 2021, according to data from Savills.

The keyword here is ‘prime’, the slightly nebulous label the property industry applies to the highest quality buildings.

These are in “well-served locations, by transport, by amenity, in fun places to be with owners who care about you and who are going to look after you and provide a service that is commensurate with quality”, says GPE chief executive Toby Courtauld. He argues that 90 per cent of the company’s portfolio, which is predominantly located in the West End, either meets these criteria or has the potential to.

Bosses have deployed stick and carrot alike to cajole their employees back into the workplace in the wake of the pandemic. Providing a fabulous office is a favourite strategy.

But demand does not extend all the way down the quality chain. “When it comes to lettings, probably two or three out of 10 will be best in class,” says Oliver Bamber, UK board director at Savills. “The rest will be quite hard work, and the bottom two or three will be almost un-lettable.”

Location matters, as two recent British Land (BLND) developments exemplify. The Reit, which focuses on building ‘campuses’ that combine office towers with shops, restaurants and other amenities, let space in its tower at 2 Finsbury Avenue, in the heart of the City, to hedge fund Citadel for then-record rents in 2024.

By contrast, its Canada Water development, tucked away in London’s south-east, is struggling to attract interest.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Refurbishment costs have risen

Not all companies are eyeing up new space in London’s most prestigious locations. Companies including Accenture, Vodafone, EY and Nomura all opted not to move offices last year, according to the Financial Times.

The associated costs disincentivise many. Around two-thirds of European tenants that decided against moving last year cited costs, according to a survey by CBRE, a third property broker.

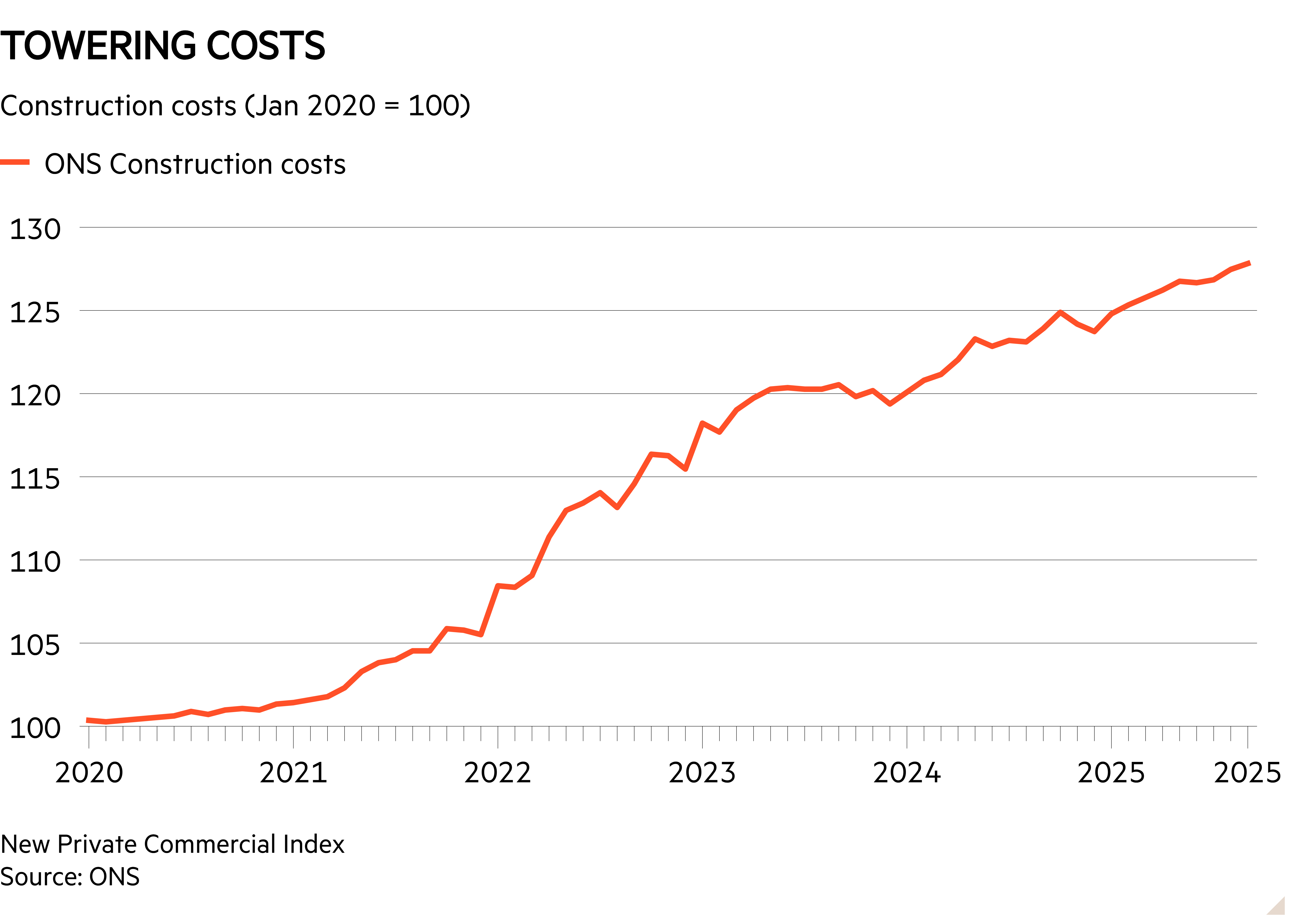

These include not just higher rents but also refurbishment, which tenants have traditionally funded. Refurbishment costs have roughly doubled since the pandemic, and construction company Turner & Townsend now estimates the all-in cost of refurbishing a prime London office at an eye-watering £434 per square foot, the highest in the world.

“It’s a massive disincentive to move,” acknowledges Simon Brown, head of UK office research at CBRE.

Not that all tenants are directly footing the bill. Landlords are broadening their product offering to appeal to more tenants.

Take GPE’s fully managed offering, which now accounts for 30 per cent of its portfolio by value. The company fits out and furnishes an office in advance, before leasing it out on short, two or three-year contracts. The tenant pays higher rents as a consequence, but avoids the hassle of interior design.

The product, which GPE wants to account for 40 per cent of its portfolio, is integral to the company’s medium-term target of trebling its FY2025 adjusted earnings per share (5.2p).

Fellow landlords Land Securities (LAND), British Land and Derwent London (DLN) all have either flexible or fully managed offerings of their own, although none as sizeable as GPE’s. There is also pure-play flexible office provider Workspace (WKP).

One potential alteration to landlord-tenant dynamics could come from a government ban on upward-only rent reviews. The industry standard is for tenants to sign 10-year leases with a rent review after five years, at which time the rents can only increase.

A ban would reduce the visibility and security of landlords’ income streams, yet industry insiders are largely unconcerned. “We don’t foresee it being a major issue for the industry but it’s probably something we could have done without” says Chris Perry, a director in Savills’ London valuation team.

Limited supply

Another potential deterrent for tenants looking to move is a lack of choice. After two strong years in 2025 and 2026, new office completions from 2027 onwards are set to fall well below likely tenant demand, according to Cushman & Wakefield, a broker.

Indeed, fellow broker Knight Frank is forecasting nil vacancy in prime City offices by 2028, with all new space fully let to tenants.

While this may appear a golden opportunity for developers such as Helical (HCL) to profit from a growing gap between supply and demand by building new towers, the reality is not so simple.

Higher interest rates, steep construction cost inflation, planning delays and new regulations around building safety and environmental standards have combined to make new developments increasingly unviable.

“It [new development] is tricky,” says Mark Swetman, chief executive of LS Estates, a developer that retrofits existing City buildings into offices.

“The barrier to entry, especially in the West End, has never been higher,” argues Courtauld. “The opportunity for the supply side to react [to changes in demand] is super thin.”

Indeed, Landsec, whose existing office portfolio is centred around a large campus in Victoria, is eschewing new office developments.

“We see little upside in selling these high-quality existing offices to fund the development of new ones,” the company said of its portfolio in November.

There is still time for this narrative to change. “If rents keep going up, it will eventually become economically viable to develop and people will develop . . . offices are cyclical,” says Adam Shapton, an analyst at Green Street, a research firm.

“Development will come back. It always has,” says Swetman.

But the response will nevertheless be sluggish. “The development process is elongated. It’s at least three years,” says Phil Hobley, head of London offices at Knight Frank.

Despite the attractions of strong rental growth and limited new supply, the investment market has been sluggish. There were around £7bn of ‘key’ London office transactions in 2025, according to CBRE, an increase of almost half versus 2024, but comfortably below the 10-year average of £11bn.

“We are seeing growing confidence in the office market,” says Ed Brown, head of central London investment at CBRE. “The severe lack of a development pipeline is providing investors with the confidence to buy and reposition assets.”

Investors can fund acquisitions with credit that is increasingly easier to access and borrowed at lower spreads to gilts.

“The current credit landscape is as large as it has ever been,” observes Chris Bennett, head of London capital markets at Cushman & Wakefield. “Credit conditions are really strong.”

Low-quality offices are struggling to find buyers, though, and face conversion, for example into hotels. “We have witnessed, and will continue to witness, those assets reverting to alternative uses,” says Martin Lay, head of London office capital markets at Cushman & Wakefield.

Investment returns

An improving transaction market should come as good news to London office Reits. The likes of Derwent and GPE cannot expect to generate their desired returns without expertly buying, developing, leasing out and selling on at a profit.

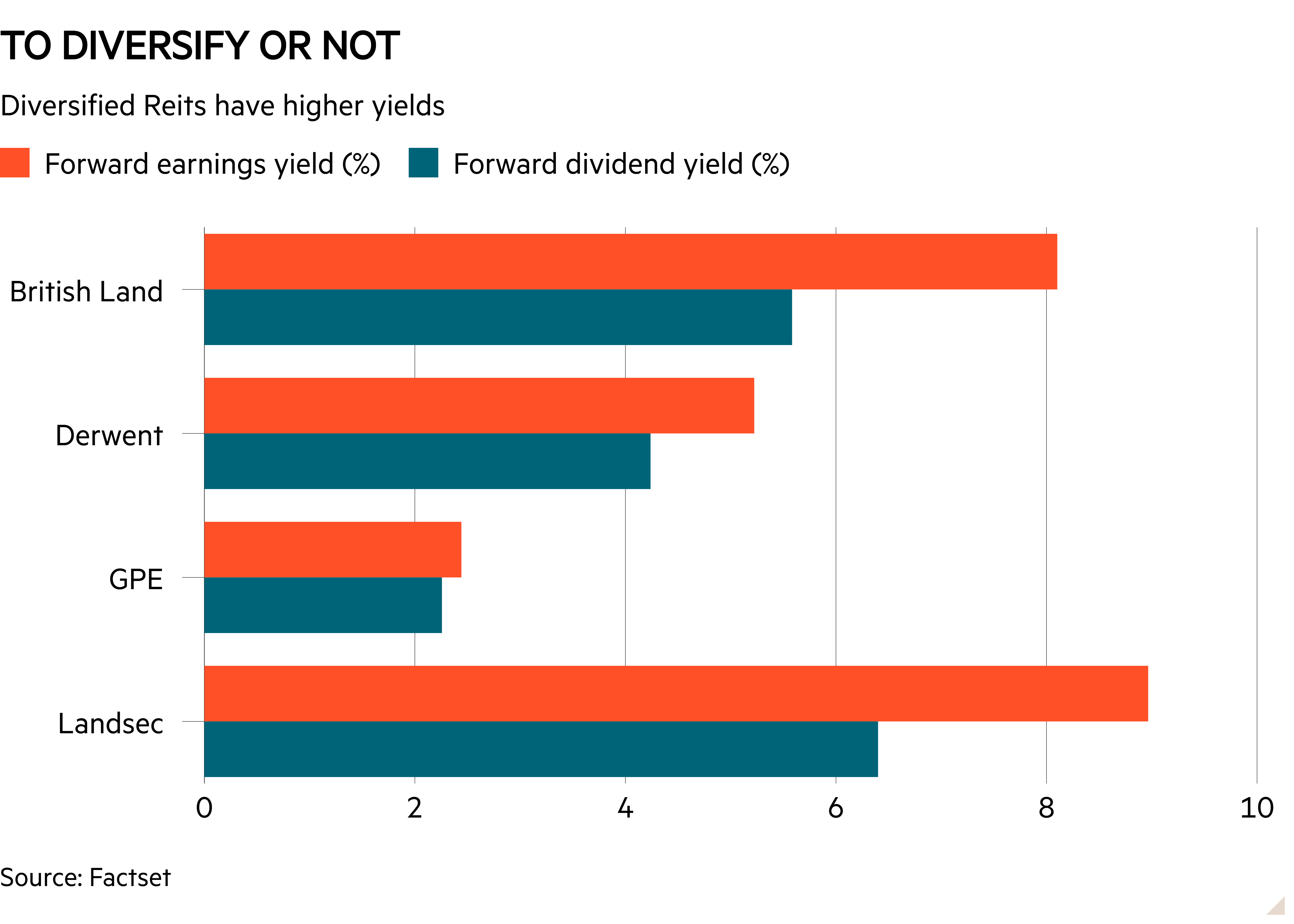

GPE for example, aims to deliver a medium-term return on equity for shareholders of above 10 per cent, well above the 3.5 per cent income yield of its existing portfolio. Closest peer Derwent, whose portfolio yields a slightly higher 4.4 per cent, has not quantified a profitability target.

Price appreciation would also help, but the cyclical nature of offices makes this unpredictable. London office values increased by just 3 per cent in the decade to September 2025, according to data from MSCI.

Analyst opinions vary. “GPE are getting it right,” says Panmure Liberum analyst Tim Leckie, who has a ‘buy’ rating on the stock. “They are getting the buildings right, and getting the product right.”

“I think they [GPE] can probably achieve it [their target in an individual year] going full throttle on the development pipeline,” says UBS analyst Zachary Gauge, who has a ‘sell’ rating on both it and Derwent, preferring other property sectors.

“But it’s the through-the-cycle part that’s tough,” he adds. “You have to keep doing that [development] year on year.”

Derwent’s and GPE’s ostensibly cheap valuations arguably reflect the scale of the challenge. They trade at a 40 per cent and 31 per cent discount respectively to their most recently reported net asset values.

It is a similar story for the recent strategic pivots of diversified peers British Land and Landsec, who have both reweighted their portfolios away from offices in recent years, into retail parks and shopping centres, respectively, albeit their yields are higher.

AI uncertainty

There is one final elephant in the atrium: AI, and its potential to reduce office jobs.

“The strongest correlation to rents is employment growth . . . and that’s the thing that is going to be most impactful to the success of a business like this,” says GPE’s Courtauld. He argues that AI is a net addition to office jobs at the moment, because of the jobs AI-native companies create.

“AI is a good thing for A-quality space in the near term,” agrees Green Street’s Shapton, who has a ‘buy’ rating on Derwent and a ‘hold’ rating on GPE.

“We don’t see it [AI] as a negative thing, at least not yet,” says Kerry Houston of Oxford Economics, which is forecasting average annual London office jobs growth of 1.3 per cent through to 2030, half the rate of the previous decade.

But there is nevertheless uncertainty. Green Street estimates that, in a negative scenario where AI starts replacing jobs, London office vacancies could reach 8 per cent by 2030, a third higher than in their ‘normalised’ scenario. This risks putting downward pressure on rents.

Office investors have plenty to ponder, as Shapton acknowledges.

“If you believe in London offices, that rent growth is sustainable, that financing costs are coming down and you’re not too worried about near-term demand threats or long-term cyclicality, then you should buy [exposure] through Reits,” he says. “They are trading well below private market values and, moreover, offer unambiguous liquidity.”