Hu Xijin, who has more than 20 million followers on social media platform Weibo and was the editor-in-chief of state tabloid Global Times before retiring in 2021, has joined the millions who are nursing losses from the US$1.3 trillion blowout.

In a social media post last week, Hu revealed that he had paper losses of 100,000 yuan (US$13,792) in his 700,000 yuan stock portfolio.

Hu grabbed the headlines when he first announced his decision to invest in stocks with an initial principal of 200,000 yuan in June last year.

“The logic of the stock market changes constantly and it’s hard to keep up with the dynamics,” Hu said in a recent social media post. “While the performance is so bad, I want to keep it on record as a sample of China’s individual investors.”

Jia Yuer, a 46-year-old engineer working for a technology company in Shanghai, has suffered a 15 per cent loss on his stock portfolio this year. He blamed the loss on the downcycle of the economy and heightened geopolitical risks stemming from “black swan” events, a term referring to unpredictable events with potential severe consequences.

“There’s a big risk in terms of long-term investments now,” he said. “The market has no confidence, as investors opt to cash out the very next day once they have profits, even minor ones. And a stabilisation in growth is still out of sight, so there’s no fundamental support for the stock market.”

A lack of confidence among investors is a source of frustration for Wu Qing, who was abruptly named chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission in February to oversee the nation’s US$8.2 trillion stock market. His mandate to revive investors’ trust saw some initial success after he cracked down on manipulation, imposed curbs on short selling, tightened new share supplies and pledged to boost the quality of listed companies. Stocks rebounded, helped in part by state-directed buying.

However, the momentum has failed to sustain, with investors shifting their focus to economic growth prospects and corporate earnings. China’s economy grew by a slower-than-expected 4.7 per cent in the second quarter, weighed down by the property market and tepid retail sales, while profits for Chinese listed companies probably dropped 0.9 per cent year-on-year on average in the April-to-June period for a second straight quarter, according to Huaxi Securities.

Adding to the gloom were the wild swings in global markets, after US President Joe Biden’s withdrew from the presidential race and the artificial intelligence trade unravelled, injecting further uncertainty.

With pessimism swirling, any rebound may be short-lived as disappointed investors are waiting in the wings to offload their battered portfolios.

Yan Xiaosen, who has seen his 2018 investment of 500,000 yuan in stocks and mutual funds shrink by 40 per cent, said he would sell if the rebound in the Shanghai Composite Index, a gauge popular among individual investors, pushes it above the 3,000-point mark. The measure closed at 2,890.90 on Friday.

“I have lost faith in the nation’s economy and the listed companies,” said the 47-year-old sales manager with a kitchen utensil maker in Shanghai. “It’s unreasonable for us to recover the losses in the next one or two years because the market is witnessing a crisis of confidence.”

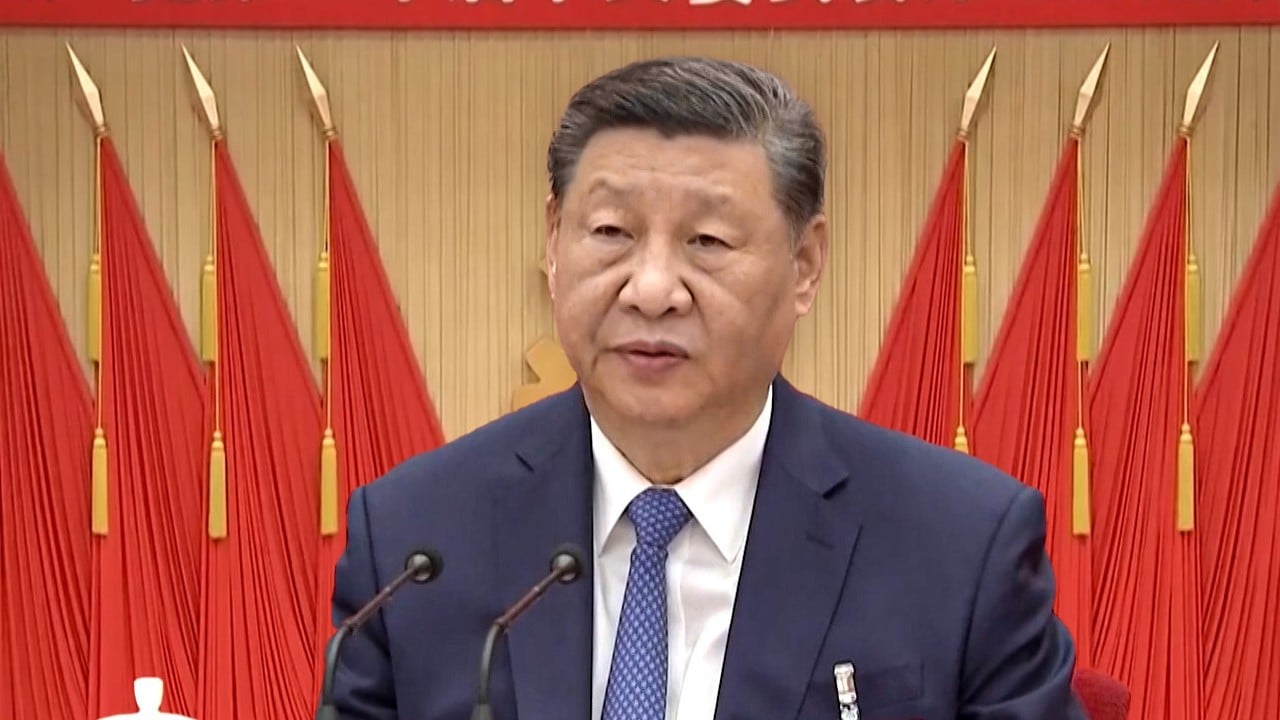

A potential catalyst for stocks could be this month’s Politburo meeting, in which Communist Party chief Xi Jinping and his colleagues are expected to set the policy tone for the economy through the rest of the year.

The market stands a chance of a stabilisation or even a rebound, if the meeting delivers a message of growth stabilising, according to Song Yiwei, an analyst at Bohai Securities in Tianjin.

Still, that may not be quite enough to entice investors who have been whipsawed by a four-year bear market and have nightmares about the 2015 market collapse.

Sissi Liu, a Shanghai-based housewife, has turned her back on trading stocks since she dumped all her holdings in 2018. Now, she would rather put her money in time deposits, even if it means an annual yield of 1.35 per cent on a one-year term.

“My decision to exit the stock market is right,” she said. “Why bother investing in a market that is not so different from a casino?”

Additional reporting by Daniel Ren