A new book by Rebecca Anne Proctor with Alia Al-Senussi promises some explanation of what’s going on

If you haven’t been living under a rock during these postpandemic times, you’ll likely have heard about a string of public art projects, Desert Xs and biennials popping up in Saudi Arabia, as well as a string of the type of curators (the Iwona Blazwicks, Phil Tinaris, Neville Wakefields, Uta Meta Bauers) that are running them. This slim book promises some explanation of what’s going on. At the heart of it all is Saudi Crown Prince (and Prime Minister) Mohammed bin Salman bin Abdulaziz’s Vision 2030 ‘reform agenda’. He’s popularly known as MBS, but best known for orchestrating a job of human butchery (acknowledged, briefly, here). His vision encompasses top-down investment with the aim of creating social and economic diversification away from the tyranny of oil and into sports, arts and other things that people like, rather than dislike. Although, to be fair, we all continue to consume a lot of oil even while we decry its environmental costs. In any case, the MBS we meet here is a freedom fighter if you like (not just from the nation’s slavish dependence on the black gold, but also, when it comes to art, the authors tell us, from a conservative public created by Conservative Islam, who, and I’m going to shock you here, don’t like or connect to contemporary art). He’s just trying to get people to relax. And create a favourable environment for local and international investment. Some of it in art.

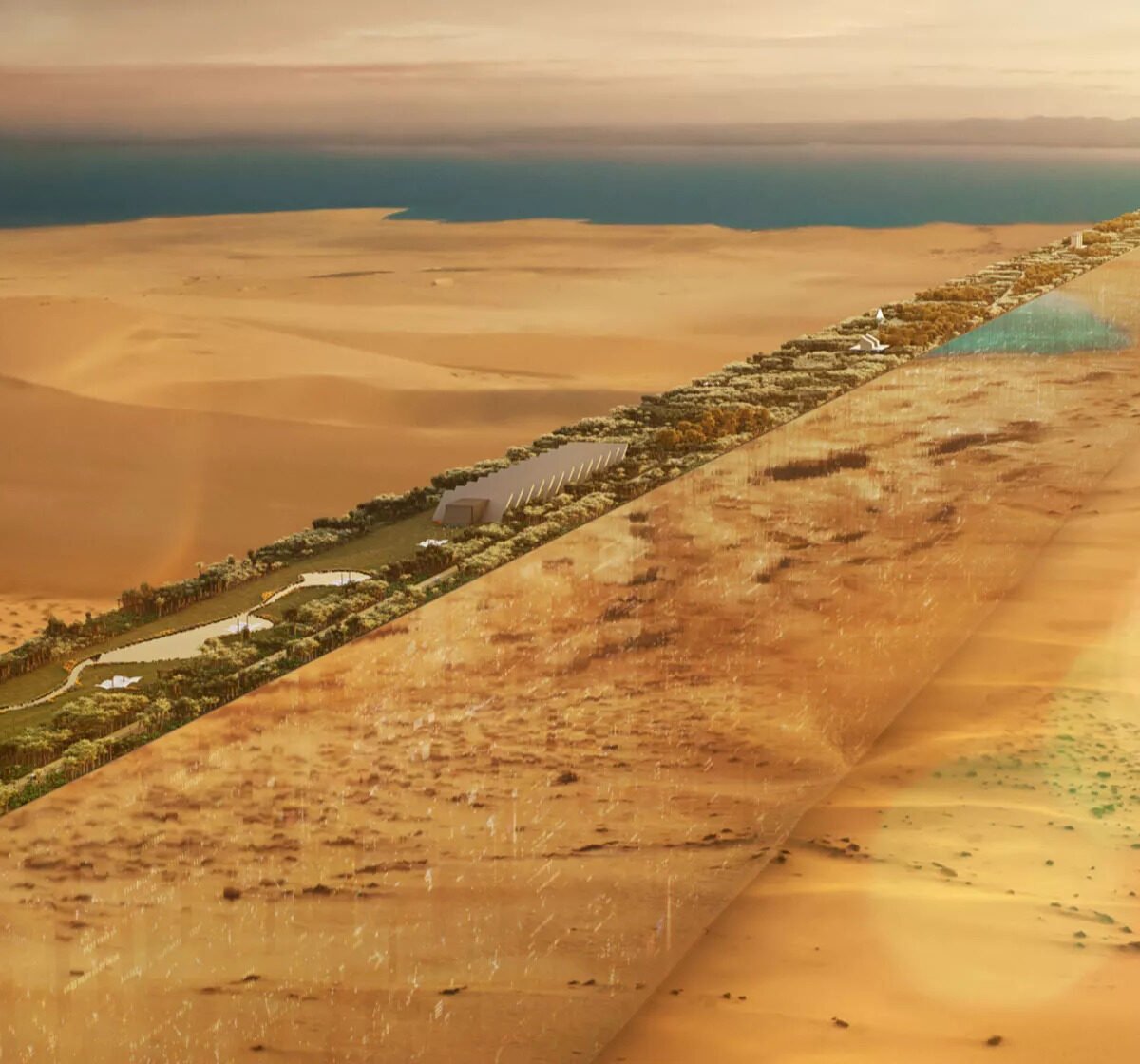

MBS himself is investing in The Line, a 170km-long ‘linear city’ (comprising a single continuous structure). The Line, as others have pointed out, looks like Italian collective Superstudio’s Continuous Monument (shown at MoMA in 1972), which was intended as a commentary on the uniformity and lack of freedom brought about by an overinvestment in capitalism; but in its Saudi incarnation, it is a monument to freedom (for the reasons given previously). To be fair, the authors of this book have a keen sense of irony/hypocrisy themselves, rightly finding it in many of the (Western) criticisms of Saudi’s arts policy. Those criticisms centre around the fact that the Gulf State is creating an arts infrastructure based on the belief that art is an investment, where it is the case that institutions in, say, the UK deploy the same terminology when faced with government budget cuts.

Yet this is not a publication with any real kind of argument, in the sense that those opposed to the 2030 scheme are not really represented here. The fact of dissent (generally) is acknowledged from time to time, but dissent itself is never given a voice on these pages. Instead there are anonymous voices from Art Basel (criticising Saudi artists who spoke out) and commentary from curators (see above) already on the Saudi payroll. There’s a comparative study of regional competitors (Qatar – for whose museums this reviewer occasionally curates – and the United Arab Emirates) that declares it’s going to make the case for why Saudi is different, but merely concludes that Saudi is focused on its own artists and cultural resources (rather than foreign imports), which are more bountiful than those across its borders as a result of statistical probability: it has a larger population than its neighbours. Disappointingly, then, the brief but not uninteresting chapter on Saudi’s contemporary art history doesn’t go deep enough to really back this verdict up (which is most likely correct). Indeed, given all that, it’s bizarre that this book has come out in a series that aspires to be (under the auspices of the Sotheby’s Institute) academic publishing. It falls far short of that.

Art in Saudi Arabia: A New Creative Economy? by Rebecca Anne Proctor with Alia Al-Senussi. Lund Humphries in association with Sotheby’s Institute of Art, £19.99 (hardcover)